The History of the York Sub Aqua Club, inspired by Denis Moor

In 1957, the York Sub Aqua Club emerged from the York Underwater Research Group. Initially, our meetings took place in pubs across York city centre, where committee members donned their best suits and carried briefcases. Eventually, we were offered a piece of land on Butcher Terrace, conveniently close to the river. There, our dedicated members constructed our own club house using materials they sourced at cost. The interior was thoughtfully redesigned to include a spacious clubroom with a bar, lecture room, office, and restroom facilities.

Adjacent to the clubhouse, we built a compressor house to ensure clean, breathable air for diving. Securing a license from Whitbread’s brewery allowed us to operate smoothly. Our facilities were put to good use by various groups, including the International Club, Country and Western enthusiasts, and the Karate Club. Sundays saw the Yorkshire Federation of Divers convening at our venue. Over the years, we hosted countless divers during our annual river races.

Our club house became a hub of activity, adorned with hundreds of collected artefacts that contributed to its marvellous atmosphere. We also collaborated closely with police divers, providing assistance whenever needed.

Early Years

Early Years

In the nascent days of our club, our divers weren’t exactly trailblazers of the underwater realm, but they certainly had their share of remarkable moments. Picture two hardy lads, clad in woolly jumpers, venturing to a lake near Elvington for their training sessions. Their unconventional gear included a bucket perched atop their heads, anchored by hefty ploughshares. In a synchronised dance, they took turns pumping air into the bucket using a war-time stirrup pump. Little did they know, they were unwitting pioneers of the emergency free ascent technique—perfecting it when the bucket inevitably tipped.

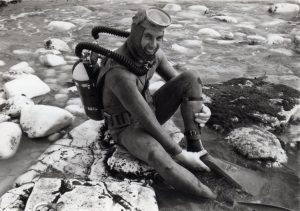

Fast-forward to 1957, and diving suits had evolved significantly. Our early members transitioned from the archaic frogman suits to the more sophisticated Dunlop “dry suits.” The elite among us even donned the French Tarzan wetsuits favoured by Jacques Cousteau’s renowned team of divers. For those on a budget, a made-to-measure kit was the thrifty choice, albeit assembled with a rather unappealing black adhesive. During a club dive at High Force in April, one unfortunate member experienced a suit malfunction in a rather delicate area—prompting a memorable outcry!

Today, our modern dry suits are nothing short of marvellous. They allow for deeper and warmer dives, ensuring comfort and safety beneath the waves. But let’s rewind to our humble beginnings: the club’s early days saw us equipped with 750-liter bottles repurposed from bomber aircraft oxygen cylinders. Often, these bottles were paired up for actual dives. Our first regulators were modified calor gas regulators, notorious for their cacophonous performance during pool training. As time marched on, we upgraded to Mistral, Heinke, Submarine Products, and “Sealion” valves.

Lifejackets? Not a common sight back then. And as for ditching a weight belt, one had to be truly desperate. Our training regimen included mastering fresh water free ascents and second-class 40-50 feet free ascents. Alas, a few air embolisms during training sessions led us to rethink our approach, and the practice eventually ceased. Curiously enough, our members conducted these ascents in the picturesque waters of Filey Bay.

Training

Our aquatic journey commenced within the walls of St. George’s Baths, where our passion for underwater exploration took root. As we honed our skills, we ventured forth to other training grounds—the Yearsley and Rowntrees open-air pools. But our thirst for knowledge and adventure knew no bounds. We explored additional locales, including the Bootham pool (a modest 9 feet deep), St. Peter’s School, St. John College, and the exhilarating Barbican High Diving pool (plunging to a depth of 12 feet). These sites became the canvas upon which our diving dreams unfolded.

In a remarkable feat, we produced a training film for the esteemed British Sub Aqua Club. Picture a dedicated team of divers, rising with the sun at 6:00 AM week after week, converging at the Yearsley open-air pool. There, they faced the lens of an early underwater camera system—an artefact belonging to one of our own. The lens captured their aquatic ballet, weaving a visual tapestry of skill and determination. Filming extended beyond the pool’s confines, taking us to the enchanting waters of St. Abbs and the rugged cliffs of Flamborough Head.

In a remarkable feat, we produced a training film for the esteemed British Sub Aqua Club. Picture a dedicated team of divers, rising with the sun at 6:00 AM week after week, converging at the Yearsley open-air pool. There, they faced the lens of an early underwater camera system—an artefact belonging to one of our own. The lens captured their aquatic ballet, weaving a visual tapestry of skill and determination. Filming extended beyond the pool’s confines, taking us to the enchanting waters of St. Abbs and the rugged cliffs of Flamborough Head.

As our proficiency grew, we transitioned to open water, equipped with snorkelling gear. But the azure depths remained elusive until each diver completed rigorous aqualung training in the pool. Our underwater odyssey unfolded across diverse landscapes: the tranquil River Ouse, the bustling Grimsby docks, the serene Sand Hutton Lake, the mysterious Stridd (nestled near Bolton Abbey), and the inviting shores of Appletreewick, Kearby Sands (Wetherby), The Derwent, and Lake Gormire. Our trusty vessel—a modest hard boat powered by a 6hp engine—carried us forth, albeit with a touch of delightful restriction.

But our wanderlust knew no bounds. In the swinging sixties and adventurous seventies, our club embarked on thrilling expeditions. We set our compasses toward the rugged beauty of Oban, where club dives unfolded against a dramatic Scottish backdrop. Meanwhile, intrepid members charted their own courses: Elba, the sun-kissed South of France, the mythical Greek Islands, Sardinia, and the storied isle of Malta. These journeys etched tales of camaraderie, discovery, and saltwater magic into our collective memory.

Among our ranks, visionaries emerged. In the seventies, one member designed an ingenious underwater transmitter/receiver compatible with a Heinke full-face mask. Another crafted an airlift, both tools instrumental in surveying the depths of the River Ouse and the meandering course of the Derwent. Freshwater divers thrived; their passion undeterred by the scarcity of boats. Two cherished sites held our hearts: the enchanting Appletreewick and the enigmatic Stridd, where underwater caverns beckoned, narrowing to a mere five feet wide.

Achievements

Back in 1958, the York Sub Aqua Club etched its name in diving lore by clinching the first ever prestigious Heinke Trophy—a coveted honour bestowed upon the most forward-thinking club in the realms of training and advanced diving. Our journey was marked by extraordinary individuals who rose from our ranks, leaving indelible marks on the underwater world.

Back in 1958, the York Sub Aqua Club etched its name in diving lore by clinching the first ever prestigious Heinke Trophy—a coveted honour bestowed upon the most forward-thinking club in the realms of training and advanced diving. Our journey was marked by extraordinary individuals who rose from our ranks, leaving indelible marks on the underwater world.

Among these luminaries, a founder member emerged as a “Diver of Distinction”—a title immortalized in the pages of the old diver magazine. During a daring dive beneath the rugged cliffs near Fast Castle, north of St. Abbs, he not only charted the course of a freshwater spring and cave but also demonstrated an unconventional culinary feat: devouring raw sea urchins. His audacity and expertise became legendary.

Across the Atlantic, an American Top Coastguard discovered inspiration in the exploits of Lloyd Bridges, the iconic star of the diving series “Sea Hunt”. This Coastguard, an honorary member of the York BSAC, penned a letter to our committee. The result? An arrangement that allowed him to pursue his 1st Class certification at an American university. With honours secured, he went on to establish the BSAC of America, leaving a transatlantic legacy.

Yet another luminary graced our ranks—a 1st class diver with a penchant for innovation. Armed with a camera, he embarked on an underwater odyssey, capturing the ethereal beauty of an area off the south coast. His creation, the first amateur underwater film titled “Neptune’s Needles”, resonated with audiences, sparking wonder and curiosity. Today, he stands as one of the world’s foremost authorities on dolphins, his literary legacy spanning over 20 books.

Our club’s legacy was etched in more than just underwater adventures. Picture this: a certificate, adorned with the signature of the Duke of Edinburgh, arrived at our doorstep—an emblem of our tireless efforts during “Operation Kelp.” But that was just the beginning. Guided by the indomitable Dr. David Bellamy, we descended upon the rugged shores of Selwicks Bay, off the majestic cliffs of Flamborough. Our mission? To gather kelp samples from varying depths, a delicate dance beneath the waves. With unwavering dedication, our members, families, and friends meticulously measured each discovery in square meters. These treasures were then transformed into ash, their secrets unveiled by the discerning eyes of Durham University—experts in the alchemical arts of checking copper, lead, and mercury content. Our corner of the ocean proved to be a thriving ecosystem, a testament to our stewardship.

But that was not all. We embarked on “Operation Starfish”, a symphony of conservation. Our canvas extended to Filey, the windswept Brigg, and a vigilant pollution monitoring station. No task was too arduous, no challenge insurmountable. In those days, health and safety regulations were mere whispers, drowned out by our determination. Our divers cleared net lines from boat props, mended the sinews of Castle Mills, Naburn, and Linton locks. We surveyed gates, laying quick-drying cement—a symphony of industry and purpose. And when fisheries faced obstructions in lakes and rivers, we waded in, sleeves rolled up, hearts aflame.

Yet, there was a dark underbelly—the Foss. Few volunteered to brave its murky waters, especially near the incinerator outlet. Imagine the heat, the filth, the blackness clinging to our skin. Post-dive showers stretched into eternity as we scrubbed away the grime. And if fate dealt a cut, well, hospitals became our second home. The Foss, a parallel stream to Egypt’s Suez Canal, harboured secrets—diseases lurking, waiting for an unwitting victim. We were forewarned: a plunge into those waters could earn us a jab for every ailment known to humankind.

Yet, there was a dark underbelly—the Foss. Few volunteered to brave its murky waters, especially near the incinerator outlet. Imagine the heat, the filth, the blackness clinging to our skin. Post-dive showers stretched into eternity as we scrubbed away the grime. And if fate dealt a cut, well, hospitals became our second home. The Foss, a parallel stream to Egypt’s Suez Canal, harboured secrets—diseases lurking, waiting for an unwitting victim. We were forewarned: a plunge into those waters could earn us a jab for every ailment known to humankind.

When the call echoed through the hallowed halls of the “Three Cups” in Stamford Bridge, our club divers rallied—a motley crew of adventurers drawn by curiosity and a dash of audacity. What made this inn unique? A wishing well, nestled right into the heart of the bar. But this was no ordinary well; it held secrets, whispered tales of bygone days when it served as the tavern’s lifeblood—a freshwater conduit predating the arrival of mains water.

As we stepped into the pub, layers of coins shimmered beneath the crystal-clear water. The well itself, a mere four feet in diameter, plunged a claustrophobic five meters to the water’s surface. A challenge, indeed. And so, our smallest diver volunteered—a pocket-sized hero winched down to the depths, calling for his diving gear. The well’s bottom eluded his touch, a murky abyss where sediment turned the water inky black.

Undeterred, he toiled in three meters of darkness, clearing the well of its submerged treasures. And then, a triumphant ascent—winched back to the bar, dripping but victorious. The spoils? Nearly three hundred pounds—a bounty destined for the local Lions Club, fuelling their noble efforts to aid the community.

But our work didn’t end there. We delved into the waters of Ouse Wharf and the sinuous course of the Derwent, collecting water specimens for a freshwater survey. Bootham, St. Peter’s, and Pocklington public schools joined our aquatic quest, their students’ curious minds in search of knowledge.

And then, a river search—a wartime aircraft, its memory etched in the currents. Our divers followed the trail, unravelling history’s threads until they found the sunken relic—an echo of battles fought and skies crossed.

The Farne Islands yielded more treasures—anchors raised from their watery slumber. One found its way to the Grace Darling Museum at Bamburgh, a tribute to courage and maritime lore. And as we combed the site of the “Forfarshire” wreck, articles surfaced—a testament to persistence and reverence. An aircraft propeller, too, emerged near Beadnell, its polished blades now gracing the timeworn walls of our old club house.

In those days, health and safety rules were mere whispers, drowned out by our passion.

Aquatic Hero’s

The Marathon Swimmer: In the frost-kissed heart of February, our club witnessed a feat of sheer audacity. One determined soul set his sights on an aquatic odyssey: swimming from York to Selby. But he wasn’t content with solitary glory. He rallied two others, persuading them to join this marathon swim. Alas, their fortitude wavered, their stamina faltered, and they surrendered at Naburn. Not our protagonist. He pressed on, relentless, slicing through the water for a staggering 20 miles. And as he emerged, wetsuit-clad and triumphant, our boat trailed alongside, sustenance in hand—chocolate, soup, and unwavering support. No one else has dared replicate this aquatic epic. Perhaps they glimpse the abyss and think twice. Or maybe, just maybe, our marathon swimmer was forged from a different sea-salted mould.

The Marathon Swimmer: In the frost-kissed heart of February, our club witnessed a feat of sheer audacity. One determined soul set his sights on an aquatic odyssey: swimming from York to Selby. But he wasn’t content with solitary glory. He rallied two others, persuading them to join this marathon swim. Alas, their fortitude wavered, their stamina faltered, and they surrendered at Naburn. Not our protagonist. He pressed on, relentless, slicing through the water for a staggering 20 miles. And as he emerged, wetsuit-clad and triumphant, our boat trailed alongside, sustenance in hand—chocolate, soup, and unwavering support. No one else has dared replicate this aquatic epic. Perhaps they glimpse the abyss and think twice. Or maybe, just maybe, our marathon swimmer was forged from a different sea-salted mould.

The Underwater Cinematographer: In 1961, an enterprising member embarked on a cinematic odyssey. Armed with an old Eumig Cine camera, he bought a ticket to Eilat, Israel. There, he perched in the shallows, day after day, capturing the ballet of fish—their iridescent scales, their secret dances. His lens painted underwater poetry, a symphony of light and shadow. But that was just the prelude. Soon, he joined forces with Ted Falcon Barker, venturing to survey an underwater Roman City near Dubrovnik. Their discoveries echoed through time, etching their names in the annals of aquatic archaeology. And when the ink dried, his story found a home in the book “1600 Years Under the Sea”—a testament to curiosity and the depths that yield their secrets.

The Global Ambassador for Dolphins: Our club’s legacy extended beyond the waves. Two members stepped onto grand stages—the hallowed halls of York and Durham Universities, the vibrant gatherings of the York Underwater Conservation Society, and the cinematic embrace of the Scottish Underwater Film Festival at Dunblane Hydro. Their voices resonated, weaving tales of marine wonder, conservation, and the silent songs of dolphins. To this day, one of our own criss-crosses the globe, sharing stories, advocating for these sentient beings. His talks ripple through lecture halls, reminding us that beneath the surface, a world of magic awaits—a world worth preserving.

And so, the York Sub Aqua Club remains a tapestry of courage, curiosity, and saltwater dreams—a fellowship bound by water, united by wonder.